- Details

- Category: Projects

Books we have about Campbell Island

Norm Judd's Marlborough Whalers at Campbell Islannd

George Poppleton's Campbell Island 1955-1956 1958-1960

Wreckage at Campbell Island, project by Norm Judd

Situated at 52o South Latitude in the cool, stormy region known as the sub-Antarctic, Campbell Island is roughly 660 kilometres from the southern tip of New Zealand’s South Island. It is southernmost of New Zealand’s sub-Antarctic islands.

This project is the location of two artefacts probably of early 1800’s maritime construction at Campbell Island’s Monument Harbour in early January 2007. The possible origins of these two artefacts and the reasons for their location in Monument Harbour are examined.

Wreckage in Monument Harbour, Campbell Island

Introduction

Very importantly, the only ship known to have been wrecked at Campbell Island was the sealing brig Perseverance in October 1828. The wreck took the lives of two men, reportedly by drowning, but the wreck site was not reported.[1]

The First Sighting of the Wreckage

In January 1972, a weather station technician, Chris Glasson, visited a bay on Campbell Island’s south coast and took two photographs of a large, decayed timber beam, iron spikes visible at one end.

The beam, protruding from the peaty soil of a beach terrace, had been exposed by wallowing elephant seals (Mirounga leonina).

Thirty-five years later, Chris was unsure of the bay in which he had photographed the beam but after some enquiries with people who knew the island we all agreed that the wreckage had been photographed at the head of Monument Harbour.

When the writer of this article saw Chris’s photographs he arranged an urgent visit to Campbell Island with Chris to try and locate the beam.

Getting to Campbell Island?

Getting to Campbell Island, however, was another matter.

We were extremely fortunate that Rodney Russ, Director, Heritage Expeditions, understood the importance of our discovery and the task we faced, and so part sponsored berths for Chris and I on his sub-Antarctic Voyage that departed Bluff on 30 December in the Spirit of Enderby.

We landed from Spirit of Enderby at Campbell Island on 1 January.

The day began drizzly, overcast and cool (typical for Campbell Island) but the sky cleared as Chris and Matt Charteris, Conservation Officer working on a wildlife survey at the island, and I were landed by inflatable at the head of Garden Cove, at about 7.30 am to begin our 2 hour walk over to Monument Harbour.

Matt guided us to the harbour and at about 9.30am we were at the southern edge of Six Foot Lake. Here we saw a small bird at close quarters that Matt identified as the Campbell Island Snipe. We sidled with difficulty around the lake and at about 10.00am arrived at the supposed site the head of Monument Harbour.

Finding the Beam

When we arrived, we were dismayed to hear Chris say that the land around the stream had changed considerably since 1972 - mainly the build up of peat either side of the stream and also the stream appeared to have widened.

With our hearts in our mouths we began our search. Even with Chris’s 1972 photographs in our hands it took us nearly 10 minutes to see all that was visible of the beam; bent iron rods and a small patch of timber.

All we could see were the pins and a small amount of timber.

A Second Piece of Wreckage

Matt found a second timber object 1.6m long, appearing to be a piece of ship wreckage of old shipbuilding technology on the other side of the stream from Six Foot Lake.

It lay on the surface of the peat, directly opposite from the beam. The holes along one edge suggested trunnal (or treenail holes) or holes for ratlines as in a chain plate.

Figure 3. Object. 2

What did we see?

These were measured and the site surveyed.

A 30mm iron pin protrudes through the peat under the beam.

The plank on the other side of the stream also had an embedded, rusted iron pin.

The writer probes the timber beam to gauge its length under the peat.

What else did we see?

Some of he local wildlife in Monument Harbour; young, male Sea Lions (Neophoca hookeri).

ASSUMPTIONS ON THE WRECKAGE

The following have been developed from research and from evidence gained at the site (see Appendices).

Fact

Both objects are of larch – a Northern Hemisphere tree.

Very probable

Both objects are of timber with 5mm growth rings thus are likely to have been cut from the same forest.

Therefore both objects are from the same vessel.

Both objects exhibit early 1800’s, or earlier, shipbuilding.

Offshore flotsam rarely enters Monument Harbour and so these timber objects are unlikely to have arrived as drift material (see Appendices Discussion).

Probable

Therefore this wreck occurred at Eboule Peninsula, or in the Harbour.

Other wreckage from this vessel lies on the harbour floor.

The beam was a keelson.

The plank was a chain plate or thole pin plank.

Therefore, by their likely functions, both objects are from very separate parts of the same vessel.

Possible

The vessel was Northeast American engaged in sealing.

Other wreckage from this wreck lies in Six Foot Lake.

The beam was a deck beam.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Dive and scan for iron works and ship’s bell on the floor of Monument Harbour and Eboule Point.

Look for timber elements in Six Foot Lake (1.8m deep) and in peat between the high water mark and the Lake.

Investigate missing vessels made entirely of larch (possibly NE American – see reference to sealing schooner Henry in Appendices).

Retrieve the iron pin the beam and plank and return to New Zealand for analyses.

Run metallurgical analysis on iron pin to date manufacture.

Dive and scan North West Bay for wreck evidence.

APPENDICES

The Area Survey

The co-ordinates of the timber beam, annotated Object 1, were established by GPS.

Photographs replicating Chris’s two 1972 slides were taken from northern and south-eastern photo-points. Because of the vegetative regrowth of two decades, it was necessary to elevate the northern photo-point to include the background over the tops of the tussock.

The only disturbance to turf and vegetation caused by the site survey was the removal of a small amount of tussock roots to reveal the point of pin ‘A2’ on Object 1. The turf along the top to the beam was not removed.

The beach terrace between Six Foot Lake and Monument Harbour and the immediate coastline were scanned visually and with a small metal detector. We had tested the detector, a Fisher, in New Zealand and had known that it would be insensitive to metallic objects smaller than a 15cm coach screw buried deeper than 15cm but brought it with us all the same as it had been all that we were able to obtain at the time.

In addition, the writer carried a 1.2m steel probe to locate timber objects deep in the peat but ripped chest tendons in an accident on the morning that we joined the vessel at Bluff, preventing him from properly carrying out this part of the survey.

Samples were obtained in compliance with HPT specifications from both objects and numbers ‘1’ or ‘2’ written in ball point on each to signify the object from which they were obtained.

Photographs and movies were taken of the objects and surrounding landscape. Later, a site record was drawn up and a map completed of the immediate area and the harbour using ArcPad and ArcView mapping technology on a Pocket PC.

Chris and I researched maritime archaeology and contacted those who had visited the island’s south coast[1] and by late September decided that the object was probably:

1. A shipwreck remnant.

2. Of early to mid-Nineteenth Century shipbuilding technology.

3. Located near the Six Foot Lake outlet at the head of Monument Harbour.

Wreckage was reported at Campbell Island on two occasions in the mid-to-late Nineteenth Century but both sightings had been in North West Bay (see Endnote 1 for small-boat wrecks). Chris and I decided to attempt a visit to Campbell Island that summer to locate the timber beam and to collect wood samples from this and any other object we found to provide clues of shipboard functions, type of vessel, vessel’s country of origin and the period in which the vessel operated.

The beach terrace is covered by a small salt marsh plant species, (Leptinella plumosa)[2] that, since 1984 when the sheep were removed, had gradually replaced low-cropped grass swards obvious in the 1972 photographs. The wallows in the 1972 images are now filled with soupy mud and appear not to have been used by elephant seals for decades.[3] Surrounding rocks and the protruding iron pins must have prevented the beam from being rolled around whenever elephant seal numbers were at their peak. While we carried out the survey, several solitary male sea lions (Neophoca hookeri), appearing to be without harems, contested territory on the beach terrace and kept us on our toes. A Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus) chick was seen on a nest about 10 m west of the survey site and we took care not to disturb it.

[1] Colin Meurk, Colin Miskelly, Mark Crompton, Mike Fraser, Rodney Russ, and Rowley Taylor.[2] Pers. Comm. MEURK, C. 2007 and NZ Plant Conservation Network website: “Primarily coastal, where it grows in saltmarshes, wet depressions, on bare ground in seal haulouts and sea bird nesting grounds, on exposed peat, and amongst boulders. It occasionally extends well inland, where it grows around tussocks - often near albatross colonies.”[3] “The massive elephant seals (Mirounga leonina), which live throughout the subantarctic region, were almost eliminated from New Zealand waters in previous centuries but re-colonised Campbell Island and the Antipodes Islands this century. Recently, however, unknown factors have drastically reduced elephant seal populations in parts of their range. The Campbell Island population has fallen by at least 95 percent and the Antipodes population is also small, having less than 100 pups.”From: http://www.mfe.govt.nz/publications/ser/ser1997/html/chapter9.7.4.html

Site history

The significance of these objects being found on Campbell Island is that the island’s recorded history does not explain any site created before 1895 but for two; a campsite and a grave of the 1874 French Transit of Venus Expedition.

The writer does not know of previous human occupations of the site except that the harbour was recognised by early sealers as a sealing ground and boat harbour.

Indications of how rapidly Campbell Island’s landscape can change has been that all those who were asked about the bay shown in the 1972 photographs could not recall seeing the beam with the large iron spikes. This may have been a reflection of how people perceived the importance of a decayed timber beam at the time but it was more likely that the beam had been obscured by peat or tussock; the ability of Campbell Island’s peat and seal activities to quickly mask artefacts must be recognised. In January 1976, only four years after Chris’s visit, I visited the lake outlet area specifically to locate and record historic sites as part of my expedition brief but do not recall seeing the beam.

Area searches

In addition to the above work, Matt searched for wreck debris west of the outlet for up to six-hundred metres along the coast until a large sea cavern prevented him going further. Matt was also looking for a cave in Monument Harbour known to have held a timber extension ladder. In 1945, Jack Sorenson, wartime coastwatcher, carried an extension ladder to Monument Harbour to monitor Campbell Island shag colonies on the Eboule Peninsula[1]. In 1950, a weather station technician, Robin Stanley, photographed Jack’s ladder lying in a cave somewhere on the harbour’s coastline and Matt carried a copy of this photograph. Matt encountered no wreck debris or cave with a ladder but saw from a distance what could feasibly have been a sealer’s campsite in a bay further west in Monument Harbour.

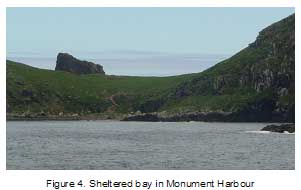

On Matt’s return, we searched for wreck debris over a distance of one kilometre to the harbour mouth along the eastern coastline strewn with giant boulders. Several fur seals and young elephant seals were encountered amongst the boulders but no debris or flotsam. Once at the harbour’s entrance we used binoculars and camera zoom lenses to scan the harbour’s western shoreline to Eboule Point. Beyond the large cavern that had halted Matt’s progress we saw the bay that Matt had identified as a potential campsite.

It is sheltered from all winds except those that sweep into the harbour from a south-easterly quarter. In addition to offering good shelter, the bay appears to have grassy terraces above a gently sloping shingle beach, freshwater sources and sheltering caves nearby. Nearby also is an historic fur seal colony.

We returned to the Six Foot Lake outlet by about 4.00pm. We then packed up our gear and retraced our steps to Perseverance Harbour, arriving back at Garden Cove at about 6.30pm where we were returned to Spirit of Enderby by inflatable at about 7.00pm. As we had made our way back from Monument Harbour through Lake Valley, noise from passerine bird call was very noticeable and in marked contrast to the comparative silence experienced by the writer during island visits prior to 1995.

The writer presented a summary of the survey’s preliminary findings to the Southland Conservator and Officers and the Conservation Board Members including the Board’s Chairman, in Invercargill, on 8 January, as part of a meeting with a wider agenda that discussed cultural heritage site management on New Zealand’s subantarctic islands.

Timber analysis

The timber samples were deposited with Gael Ramsay, Manager, Southland Museum and Art Gallery (SMAG) (Object Entry record 3131) and then sent on to Rod Wallace, Anthropology Department, University of Auckland who in turn forwarded them to Lloyd Donaldson, SCION, Rotorua, for final analysis.

The samples are to be returned to the Museum on completion of the analysis.

Summary of findings Site

-

The beach terrace, rising about 2m from MHW to the edge of Six Foot Lake over a distance about 90 metres, has a gradient of about 1:40. The sea bed for about 100m beyond the mean high water mark (MHW) appears to have an equally gradual gradient. The beach terrace is fully exposed to southerly winds and one witness has seen southerly storm surges washing inland and into Six Foot Lake.[1] The dominance of salt tolerant Leptinella tends to confirm this.

-

Objects 1 and 2 are about 70 metres from the sea high water mark and about 20 metres from the edge of Six Foot Lake. Object 1 is 20 metres west of the stream’s centreline an Object 2 is 0.5 metre from the eastern edge of the stream.

-

The harbour’s coastline from the lake outlet to the west for approximately 800 metres and the east for approximately 1000 metres was devoid of maritime litter suggesting that the harbour does not receive general flotsam and jetsam in as much quantity as does North West Bay. The eastern shoreline is strewn with large boulders. The western shoreline is a rock shelf from the stream outlet 800 metres to a large cavern. Beyond, the western shoreline consists of pebble beach terraces, rock shelves and boulders.

Solitary male sea lions frequent the beach terrace at the head of the harbour. Giant Petrels (Macronectes giganteus) were seen nesting in the vicinity of the Six Foot Lake outlet.

Object 1

-

Is located about 20m west of the outlet stream’s centreline.

-

It is of timber c.3m long with a cross section of approximately 300X300mm.

-

Its seaward end appears in one 1972 image to have been shattered by a substantial force.

-

A large check or mortise (‘C’ in Plan A) filled with moss appears at top right in one of the 1972 images. This was not physically investigated in this survey.

-

Metal rods are seen grouped at one end only, are probably of iron and appear to have lost surface material through oxidisation when compared with those in the 1972 images.

-

The rods appear to have been exposed to considerable force. One rod, about 30mm diameter, appears to have been shear fractured and three lighter rods, each of about 25mm diameters, are bent flat to seawards on the beam’s upper surface.

-

Two pins ‘A’ are shown in Plan A. Each is about 30mm diameter and 450mm long.

-

Three pins ‘B’ appear to have once been about 25mm diameter. Pin ‘B1’ is about 700 mm long.

-

Chris reports that the decay in the exposed timber surfaces has advanced since 1972, probably as they are no longer protected by anaerobic peat. Pin ‘A1’ has been loosened by decay and is in danger of falling into the wallow underneath.

-

The samples from Object .1 hefted very light and showed a grain similar to spruce or cedar. It has been confirmed that the timber is larch (Larex).

Fig. 5. Photograph by C. Glasson’s of the beam in 1972 showing what appears to be a mortise at the iron pin end.

Object 2

-

Object 2 was found close by the stream on its east bank.

-

It is of timber and has a plank-like configuration and appears to have been shattered at one end.

-

The object’s length is about 1650mm and greatest width about 270mm and greatest thickness, 50mm.

-

Appears very old and weathered, with a shape probably modified by seal movement, tapering from 55mm at it inland end to approximately 20mm thick at its seaward end.

-

There are indications that 3 large holes exist at even spacing, close to one edge of the ‘plank’, which imply treenail fixing and that the object may not have been a standard deck plank but an element with a high energy/tension role in the operation of a vessel such as a chain plate.

-

On inspection, the material in each hole appeared to be peat but, on reflection, what we were seeing may have been the decayed end grain of trunnal or thole pin remnants. If this material is timber, the timber-type could give a clue as to where the vessel had been built or based.

-

There are two heavily corroded, ferrous fixtures embedded in one end. One is a small, bent over portion of a heavy iron pin (30mm diameter?). The other object appears to be the head of a square spike.

-

Lying close to Object 2 was a small piece of timber that was shown by fit to have broken from the seaward end of the object. This was obtained as a timber sample for Object 2.

Timber analysis

The forest research agency at Rotorua, ‘SCION’, has identified both objects as Larch (Larex spp.), a Northern Hemisphere tree, but there are no cost-effective processes available to determine whether the larch is Canadian, Siberian, Asian or Western European. However, Lloyd Donaldson of SCION was able to confirm the following

“1/. Douglas fir and larch timbers are similar in appearance. However under the microscope they are quite distinctive. I can exclude Douglas fir with confidence.

“2/. The only thing I can tell you about the growing location is that it had a relatively long/warm summer as shown by the growth rings which are about 5mm wide. It was probably not Siberia. Thus temperate Europe, Asia or North America.

“Larch is moderately durable 5-15 years in ground contact. However in anaerobic peat it could be thousands of years old as with swamp Kauri for example. The decay that I observed could have occurred since the wood was uncovered. There were fresh hyphae growing in the wood.

“Larch is not resistant to marine borers. Therefore I would expect its life to be fairly short, i.e., one or two years unless it was protected by a coating or not accessible to marine borers (internal framework). It was certainly used for planking and decking on wooden boats, presumably coated with paint when it was planking. It was used with other softwoods as sacrificial planking below the waterline on warships in Europe prior to the nineteenth century. Some references record its modern use under the general "boatbuilding" heading. It had a reputation in Europe as being durable and its relatively high strength probably saw it used in bent framing components as well as planking.

“Thus at least 19th C is possible.

”J.C. Loudon’s, Arboretum Et Fruticetum Britannicum; Vol. IV, describes larch’s shipbuilding attributes in an early 1800’s context[1].

(p. 2350) “Deciduous trees, some of them of large dimensions; natives of the mountainous regions of Europe, the west of Asia, and of North America; highly valued for the great durability of their timber. The common larch (L. europaea) is found extensively on the alpine districts of the south of Germany, Switzerland, Sardinia, and Italy; but not on the Pyrenees, or in Spain. The Russian larch (L. e. sibirica) is found throughout the greater part of Russia and Siberia, where it forms a tree generally inferior in size to L. europaea. The black, or weeping, larch (L. americana pendula) is a slender tree, found in the central districts of the United States; and the red larch (L. americana rubra), also a slender tree, is found in Lower Canada and Labrador.

”(p 2357 -8) Larch in a vessel which sank 1400 years previously was found to still be quite hard and had been used as foundation piles in Venice.

”(p 2364) “In France… Malesherbes, in 1778, having seen some houses in the Vallais, which had been constructed of this wood 240 years previously, examined the timber, and found it not only in perfect sound, but so hard that he could not penetrate it with the point of a knife.”

The French Navy in 1798 had assessed larch for masts but discounted the timber as the trunks were either too narrow when grown in a plantation or if of large girth, were weakened by knots.

(p 2365 to 70) “…The only objections to this wood in Britain are, according to Monteath, its being so remarkably hard to season, that it is almost impossible to keep it from bending and twisting; and that, when it is properly seasoned, it is so very hard, that it is difficult to work, and more especially to be smoothed on the surface with a plane. To remedy the evil of twisting, some adopt the method of steeping it (whilst in the log) in water for twelve months, and then taking it out, drying it for twelve months more, before cutting it up. Steaming has also been resorted to for the same purpose; but Monteath prefers the practice which has been often recommended, though a little employed, viz. that of barking the tree standing, and then leaving it a year before it is cut down.

”The Swiss also, found larch unsuitable for masts.

It is extremely resinous and produces much turpentine, although of an inferior quality to other firs. If the natural resins are retained, the cut timber exhibits very little shrinkage.

British assessments of larch’s shipbuilding attributes are drawn from the work of MATTHEW, On Naval Timber, 1831. There are recommendations for using larch when young and not timber from the top of the tree when looking for strength and durability. The netted fibres of the wood resists cracking or splitting even when cut into thin planks, or deal.

(p.2370) For Naval purposes, Matthew observes, the larch, from its general lateral toughness (particularly the root), and from its lightness, seems better adapted fro the construction of shot-proof vessels, than any other timber. It has been used for ship-building in the Tay, he says, since 1810; and there were, in 1830, several thousand tons of shipping constructed of it. “The Athole frigate, built of it in about 1818; the Larch, a fine brig, built by the Duke of Athole several years earlier; and many other vessels, built more recently; prove that larch is as valuable for naval purposes as the most sanguine had anticipated. The first instance we have heard of British larch being used in this manner was in a sloop repaired with it about 1808. The person to whom it had belonged, and who had sailed it himself, stated to us, immediately after its loss, that this sloop had been built of oak about 36 years before; that at 18 years old her upper timbers were so much decayed as to require renewal, which was done with larch; that 18 years after this repair, the sloop went to pieces on the remains of the pier of Methel, Fifeshire, and the top timbers and second foot-hooks of larch were washed ashore as tough and as sound as when first put into the vessel, not one spot of decay appearing. The owner of the larch brig, who had employed her for several years on tropical voyages, also assures us that the timber will wear well in any climate, and adds that he would prefer larch to any other kind of wood, especially for small vessels; he also states that the deck of this brig, composed of larch planks, stood the tropical heat well, and that it did not warp or shrink, as was apprehended.

“Larch knees are possessed of such strength and durability, and are of such adaptation by their figure and toughness, … The knees of vessels have a number of strong bolts, generally of iron, passing through them to secure the beam-ends to the sides of the ship. Larch knees are more suited to this, as they do not split in the driving of the bolts, and contain a resinous gum, which prevents the oxidation of the iron.

(p.2371) If not cured correctly (over two years!) larch timber is prone to warping.

(p.2400) A description of the American Larches (L.americana) and its variations. The paper disparages the qualities of the American species introduced to Britain, stating that, generally, the tree was slow growing and the wood of L. a. pendula “is so ponderous, that it will scarcely swim in water.” However, the Canadian and North American larch when grown on home territory produced an extremely valuable timber, and had no fault except for its weight. The tree was to be found growing in Vermont, New Hampshire and in the district of Maine but was most abundant in New Foundland and was used primarily in the construction of vessel knees.

Discussion

This discussion endeavours to follow a rule of reasoning based on the published knowledge of others, and official record. It does not provide a conclusive result of how the two objects arrived in Monument Harbour and what their original purposes may have once been but attempts to construct all the facts known to the writer in a way that might be helpful to further research.

How did Object 1 and 2 end up in their current situations? Both are resting with their lighter ends seaward. Based on the assumption that the heavy pins in Object 1 are at one end only, and that we know there are the remains of a heavy pin at one end only of Object 2, it may have been that the pins’ weights and protrusions caused drag so that the lighter ends of both objects came ashore first. Did a strong return eddy of water or a surge of water from the lake then swing both objects around so that their lighter ends pointed to sea? It is further speculated that most movement by water flow occurred when the objects first arrived on the beach terrace. Further movement of Object 1 may have been impeded by accumulation of peat over time.

If other objects were carried onshore at the same time as Object 1 and 2, did these also become immersed in peat, or were they carried back out to sea or into Six Foot Lake?

Of all of New Zealand’s Sub-Antarctic Islands, the Auckland Islands have gained the most publicised shipwreck profile. The island group was an obstruction to square-rigged vessels sailing from Australia to Europe around Cape Horn on what was known as the Great Circle Route during the so-called Auckland Islands shipwreck era extending from the mid-1860s to the early 1900s. Reasons offered for the Auckland Islands wrecks have been; overcast skies making navigational sun shots and star sightings difficult or impossible, inaccurate charts and, exacerbating the course errors of the General Grant[1] and Invercauld[2], a strong, southerly ocean current set that placed vessels much further south than their captains suspected.

Obviously, wreckage needs to possess tell-tale marks and/or accurate accounts from survivors in order that the ship wreck site may be later identified. Wreck debris of unknown ships has been seen at the Auckland Islands: there were no survivors and the ships remain unknown. An example of this has been the substantial amount of wreckage and wool bales seen floating at the northern end of the Auckland Islands in 1895 and there was debate then as to whether this was wreckage from the sailing ships Stoneleigh, Maria Alice or Timaru. [3] The location is shown on current charts as the Stoneleigh/Maria Alice wreck site.

Ships’ wreckage in 1868,[4] 1877[5] and, more recently, general maritime litter such as fishing buoys and plastic have been seen in Campbell Island’s North West Bay, particularly in the Bay’s Middle Bay. It has been as if North West Bay, exposed to the prevailing winds and current set, has been the receptacle of general flotsam and jetsam afloat in the Southern Ocean. There is debate as to whether the wreckage seen in North West Bay in 1868 and 1877 were created offshore by storm damage on a vessel, a ship’s collision with an iceberg, stack, or Campbell Island itself. Although Campbell Island may have not provided as common a barrier as the Auckland Island Group, at only a couple of degrees further south, the writer believes that it had the potential to obstruct ships on the Great Circle Route. The wreckage seen in North West Bay could have arrived as a square rigged ship or as flotsam but we may never know for sure. Although Campbell Island’s shipwreck history records one wreck only, that of the brig Perseverance in 1828, the island’s shipwreck history is probably more about shipwreck with no survivors.

Both objects in Monument Harbour are of larch that appears to have been grown at a similar latitude and display roughly the same amount of decay, and they have the same types of iron fixtures, and so it may be assumed that they came from the same vessel. If both pieces remained fastened together at the time of damage to the vessel, to be separated by wave action once they were washed ashore, it initially seems feasible that they could have drifted hundreds of kilometres to Monument Harbour. The scenario may not have even been possible. Our shoreline search revealed that the currents moving through Monument Harbour do not readily acquire offshore flotsam.

The answer to this may be the eastward flowing current pushed along by West Wind Drift. In February 1975, the yacht Valya approached South East Harbour down Campbell Island’s east coast.

The owner-skipper Annie Wilde writes.

“Under double-reefed main and staysail we motor-sailed into a sea that steadily became worse. As South East Harbour came into sight it dawned on us what the sea was about. Apart from an echo sounder’s trace of a canyon-like bottom which, with the contrary tide, kicked up the sea, we were also in the lee of Jacquemart Island which gave a steep cross sea.”[1]

This describes a current bending around either side of Jacquemart Island. Theoretically, there would be a vortex flowing between Jacquemart Island and La Botte and another between La Botte and Eboule Point. These would tend to prevent flotsam seaward of La Botte entering an eddy turning into Monument Harbour. On the other hand, if this theoretical flow pattern does exist, debris near Eboule Point would be introduced to an anticlockwise eddy curving up to the head of the harbour. As an aside, one would expect chances of crew and passenger survival in a wreck on Eboule Point in a heavy sea to have been very slight.

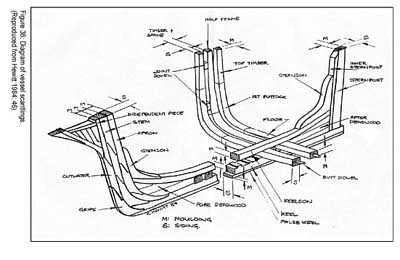

Were Object 1 and 2 connected on the vessel? Probably not. The writer initially hypothesised that Object 1 was a bowsprit. It may instead be a stern deadwood or a deck beam. Object 2 may be a timber rack with holes for receiving belaying pins – or similar, or it may be a chainplate. Mark Hammond, mariner and once owner-skipper of MV Geomarine and who has frequently navigated the Southern Ocean, comments on Object 1 in terms of it being possibly a stern deadwood or keelson:

“In the earlier days when sail ships had bowsprits with jib booms attached, the bowsprits generally came inboard though a square or round iron fixture with the inboard end butting against the bitts. Stays and guys securing the outboard end. In other words it was not fastened directly to the hull of the ship and could be "unshipped" in a relatively short time. This would make it unlikely that Object 1 is a bowsprit. There are relatively few timbers in a small ship with quite long fastenings as those rods appear to be. They are mostly in the stern of the vessel in the deadwood area between the keelson and the horn timber, the area in front of the rudder, and I would suspect that this is where object 1 is from although the checked out mortise is a big query.”[1]

[1]

HAMMOND, M.; pers comm... May 2007.

[1] BULLERS, R. Quality of construction of Australian-built colonial-period wooden sailing vessels: case studies from vessels lost in South Australia and Tasmania; a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Maritime Archaeology, Depart Archaeology, Flinders University, November 2005. p120.

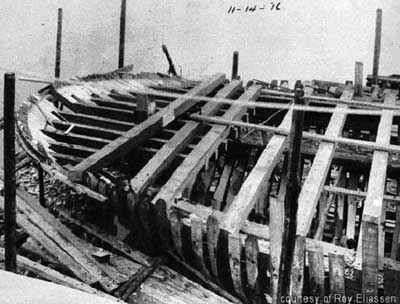

Fig 8. Deck beams in situ, East American schooner construction, late 1800s.

The deck beams and methods of fastening are clearly shown (Fig. 8) and an enlargement of detail shows pins at the beam ends (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. An enlargement of figure 8 showing detail of pins at beam ends.

Mark Hammond also comments on Object 2.

“The timber has the appearance of a pinrail being the timber that belaying pins are sat into for the purpose of making off sheets, halyards, buntlines etc. These timbers sit inside the gunwale horizontally inboard of the mast shrouds [stays], are about a foot wide, 300 mm, 50 - 75 mm deep and have pin holes at regular intervals about 30 mm diameter. However on larger vessels they were normally made of a hardwood as the lines chaff the timber. It’s unlikely that it was planking as planking always has paired fastenings. Either way I would say that these timbers came from different parts of a vessel.

What of the possibility that a vessel had been hit by southerly storm while at anchor or hove to in Monument Harbour?

Monument Harbour appears as a ‘boat harbour’ on one of the earliest known charts of Campbell Island that has been attributed to the European sealer, Frederick Hasselburg. The peninsula at the western mouth of the harbour, Eboule Point, has been the historic haunt of the NZ Fur Seal. Was this where the sealing brig Perseverance was wrecked, struck by a sudden southerly storm while at anchor in Monument Harbour, dropping off men, boats and supplies? This may have been the scenario for the wreck of the Perseverance when two men only were lost. Did the survivors recover boats, sails, spars, tools and supplies, to ensure their long-term survival in that bleak climate? Maybe. This said, the two objects at the head of Monument Harbour are very probably not from the 1828 wreck of the Perseverance. She had been reportedly laid up as a hulk in Sydney in 1814 and then rebuilt to be relaunched in 1823.[1] Imported Oregon was used for masts and spars by Australian shipbuilders in the early 1820s. Larch does not seem to feature as a shipbuilding material in Early NSW.

If we knew how many other objects accompanied Objects 1 and 2 ashore we may better speculate whether the wreck occurred at Eboule Point or in Monument Harbour. The writer proposes that the circumstances causing a vessel to be wrecked against the islands and reefs off the harbour mouth would have allowed few if any persons to reach the shore and, because of local current sets, very little wreckage to arrive at the head of the harbour. In the instance of a vessel wrecked in Monument Harbour, it would be feasible for a substantial amount of debris to have reached the head of the harbour. One could also assume that crew and passengers came ashore alive but, given the sudden ferocity of sub-Antarctic storms, it is also probable for a wreck within the confines of the harbour to have had no survivors. In March 1825, the Caroline, while loading seal oil at the southern tip of another sub-Antarctic island, Macquarie Island, was totally wrecked by a southerly storm and with such rapidity that the men found themselves ashore with only the clothes that ‘they stood up in’, and ‘a trunk’.[2] Were there survivors of the event represented by the wreckage in Monument Harbour but not of the marooning that followed?

In 1825, the New York based schooner Henry, having visited New Zealand’s subantarctic islands on a successful sealing cruise in 1823, was seen again at New Zealand’s South Cape while on a second cruise. From South Cape she set off in a south by east direction on a voyage of exploration for new sealing grounds between 60 and 65oS latitude - and was never seen again.[3] Was she constructed of North American larch? This vessel is now the focus of the writer’s research.

Very little is known of the several dwellings or grave sites that were created on Campbell Island prior to 1895, when the pastoral run began. If there were survivors to the incident that created the Monument Harbour wreckage there may be links between this and these earlier Campbell Island sites. There are many obvious sites of occupation without known histories at the head of Perseverance Harbour, the favoured anchoring place of sailing vessels since the island’s discovery. The now barely discernible remnant of a large peat-walled hut in Tucker Cove is one of these. The hut, which measures 10 metres by 5.5 metres, large enough to shelter 20 men, has a stone hearth in one corner and a stone sill in what appears to be a doorway, and may have been constructed by and for men who knew that they may not be repatriated for months or years (the Perseverance survivors were rescued after 11 months). Close to the western corner of the hut site are two mounds of chert, now also most covered by peat. Every stone has been fractured as if by a blow from another stone or hammer. One speculation for the purpose of these mounds is that they are graves. Another is that, because chert shatters to razor-sharp shards, the mounds are the dross of a quarry for making cutting tools.[4]

In 1840, Lt James Clark Ross[5] referred to huts and graves of men engaged in the sealing industry on either side of Tucker Cove. The graves almost certainly included the six seen by visitors in 1868 and where, between the mounds of two, was found a skeleton that they interred, presuming that this had been a last survivor of some unknown tragedy.[6] The graves were disturbed by elephant seals some time before farmers arrived in 1895. When, in 1902, a farmhand found three bodies unearthed at this site, he reburied them in one grave and in 1906 erected a stone cairn with a timber cross surmounted by a copper angel.[7] The farmhand repeated Armstrong’s story of the lonely survivor in an article to the Southern Cross in 1903.[8] Other graves are in evidence nearby. The large sod hut site is on the side opposite to this headland in Tucker Cove.

[6] ARMSTRONG, H. In Search of Lost Sailors, The Leisure Hour 1889.

[8] MACDONALD, A. The Campbell Islands Southern Cross, Invercargill, 28 Mar - 2 May 1903.